London Museum since 2015

London Museum since 2015From the end of Roman rule to the Anglo-Saxon and Viking invasions – a new method of analyzing DNA in ancient bones could force a rethinking of an important period in the early history of Britain, researchers say.

Scientists were already able to trace major changes in DNA that took place over thousands or millions of years, helping us to learn, for example, how the first humans evolved from creatures that like monkeys.

Researchers can now detect subtle changes in just hundreds of years, providing information on how people migrated and interacted with local people.

They use a new method to analyze human remains found in Britain, including from the time when the Romans were replaced by the Anglo-Saxon elite from Europe.

Professor Peter Heather, of Kings College London, who is working on the project with the developers of the new DNA method at the Francis Crick Institute in London, said the new method could be “transformational”.

While the project will examine the DNA of 1,000 ancient human remains of people who lived in Britain over the past 4,500 years, researchers have been there since the Romans left as a very interesting time to study.

What happened during this period more than 1,500 years ago is not well known from written and archaeological records. Historians are divided in their views on the extent and nature of the Anglo-Saxon invasion, whether it was large or small, hostile or cooperative.

“It is one of the most controversial and therefore one of the most exciting events in British history,” said Professor Heather.

“[The new method] it will give us an opportunity to see the kind of relationship found with the native population, “Are they cooperative, are there inbreeding, are the natives able to enter the elite?”

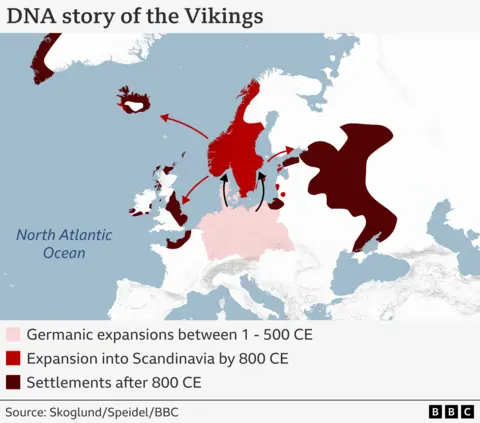

They hope for the success of this method, known as Twigstats, after testing it with human remains found in central Europe between the years 1 and 1,000 CE.

Much of what they found in DNA about the Vikings’ expansion into Scandinavia is consistent with historical accounts.

This result, published in the journal Naturehe affirmed that this method worked while showing how powerful it can be in providing new light on accepted facts when the findings do not agree with what is written in the history books.

“That’s the moment we got really excited,” said Dr. Leo Speidel, who developed the technique with his team leader Dr. Pontus Skoglund. “We could see that this could really change how much we can know about human history.”

The problem the researchers were trying to solve is that the human genome is very long – containing 3 billion different chemical units.

Seeing small genetic changes in that code that occur over a few generations, for example, due to new arrivals interbreeding with local populations, is like looking for a needle in a haystack.

The researchers solved the problem by, so to speak, removing the hay and leaving the needle in the clear – they found a way to identify the old genetic changes, ignore them and only look at the recent changes -rao.

They combined the genetic information of thousands of human remains from an online scientific database, then calculated how closely related they were, which DNA fragments were inherited from which groups and when.

This created a family tree with older mutations appearing on earlier branches, and more recent mutations appearing on newer ‘branches’, hence the name Twigstats.

Francis Crick Institute

Francis Crick InstituteEach of the people whose rings will be studied has their own stories to tell and soon scientists and historians will be able to hear their stories, said Dr Skoglund.

“We want to understand many different periods in the history of Europe and Britain, from the Roman era, when the Anglo-Saxons arrived, to the Viking era and see how this creates the genealogy and diversity of this part of the world. how,” he said.

And showing interbreeding, embedded in ancient DNA is very important information about how people coped with important periods in history, epidemics, dietary changes , urbanization and industrialization.

This method can be used in any part of the world where there is a large collection of well-preserved human remains.

Prof Heather wants to use it to investigate what he describes as one of the greatest mysteries of European history: why central and eastern Europe changed from speaking German to speak Slavic, 1,500 years ago.

“Historical sources show how it was before and what the case was after, but nothing about what happened in between,” he said.

Follow Pallab on Blue Sky and X

A new series of Digging in Britain, featuring one of the Anglo-Saxon burial grounds, Poulton Farm, will be available to watch on BBC iPlayer from 7 January 2025.

#bone #experiment #rewrite #British #history #scientists